Body Image and Distorted Perception of One's Own Body – What Does This Mean?

Assessment and Management of Distortion of Orofacial Somatorepresentation

Bernhard Taxer, PhD, MSc PT, MT (OMPT)

Harry von Piekartz, PhD, MSc, PT, MT (OMPT)

Body Image (BI): A Multifaceted Perception

Body Image (BI): A Multifaceted Perception

Body Image (BI) refers to how individuals subjectively perceive their own bodies, which often diverges from their actual physical form. This perception is a complex amalgam of one's thoughts, feelings, evaluations, and behaviors related to their body. Clinically, the significance of BI stems from its linkage to various severe disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. Disturbances in BI can profoundly affect both physical and psychological health, influencing factors like self-esteem, mood, social interaction, and job performance. These distortions, characterized by altered perceptions and attitudes towards the body, can result in negative experiences and outcomes, thereby underscoring the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of both normal and abnormal body image perceptions for effective intervention (Hosseini & Padhy, 2022).

Somatorepresentation and its Distortions

Somatorepresentation concerns the way individuals perceive and represent their bodily sensory and motor functions. In musculoskeletal disorders, distortions in somatorepresentation are evident, affecting epicritic sensitivity (such as tactile acuity) and discriminative abilities. Chronic musculoskeletal disorders frequently present these abnormalities, including reduced two-point discrimination, sensorimotor deficits, and modified emotional processing. In this musculoskeletal context, somatosensory abnormalities like diminished tactile acuity, impaired laterality recognition, and affected facial emotion recognition are observable. These represent a blend of cognitive, perceptive, and affective issues, indicating the critical role of multisensory integration in such sensory distortions (Stanton et al., 2013).

From a musculoskeletal perspective, we need to consider somatosensory irregularities, especially in areas like epicritic and discriminative sensitivity, which include tactile acuity often assessed through two-point discrimination tests (von Piekartz & Paris-Alemany, 2021). Skills such as left-right recognition (LAT) and facial emotion recognition (FER) are considered mental imagery tasks. Disruptions in these areas can indicate face-related emotional and physical impairments, encompassing cognitive, perceptual, and affective elements (Hosseini & Padhy, 2022; Parsons, 1987).

Research shows that individuals with chronic musculoskeletal conditions frequently exhibit somatosensory issues, such as a lack of two-point discrimination (Catley, Tabor, Wand, & Moseley, 2013; Luedtke et al., 2018; Luomajoki & Moseley, 2011; Maarbjerg et al., 2017; Stanton et al., 2013), along with sensorimotor deficits (in LAT, movement control) (Breckenridge et al., 2015; Elsig et al., 2014; Linder, Michaelson, & Roijezon, 2016; Reinersmann et al., 2010), and changed emotional processing (FER, alexithymia) (Aaron, Fisher, de la Vega, Lumley, & Palermo, 2019; Di Tella & Castelli, 2016; Piekartz, Wallwork, Mohr, Butler, & Moseley, 2015; von Piekartz & Mohr, 2014).

Patients with chronic orofacial pain often report feeling as if the painful area of their face is "swollen," even when there are no clinical signs of swelling, a clear indication of perceptual distortion. Interestingly, even the administration of local anesthetics in healthy individuals can lead to similar perceptions. This suggests that multisensory integration plays a crucial role in this type of sensory distortion and could be key in understanding the factors influencing this common condition (Dagsdóttir et al., 2018).

Somatorepresentation in Orofacial Pain

With a prevalence of 10-15% and an annual incidence of about 5% in the adult population orofacial pain syndromes like temporomandibular disorders belong to the most common musculoskeletal disorders (LeResche, 1997; Lipton et al., 1993). As already described in orofacial pain distortions of somatorepresentation with similar characteristics as distortions of body image can be observed (von Piekartz & Paris-Alemany, 2021). You can divide those aspects explicitly in the following parts. To get immediately an idea we also included the possibilities to test those certain motor and somatosensory disturbances:

- Tactile acuity: mainly tested with so called two-point-discrimination. Studies show changes in this somatosensory component in TMD and migraine (La Touche et al., 2020; Luedtke et al., 2018).

- Auditory acuity: consists on the localization of sounds, pitches and muting of background noises (Stamper & Johnson, 2015). Using a loudspeaker with variable frequency (250–8000 Hz) and sound intensity (5–40 dB), it is possible to measure in different regions of the so-called peripersonal space (see picture 1)

.

- Laterality recognition: special programs, like in the CRAFTA® face-training program included, test the ability to recognize left or right body parts or body movements (von Piekartz et al., 2017). Accuracy and reaction time are proper objective parameters to evaluate a progression in the rehabilitation of orofacial pain syndromes.

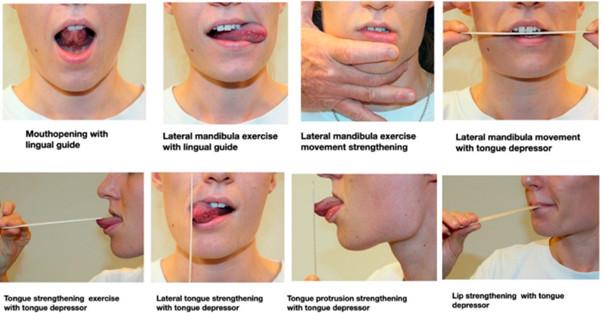

- Motor control disturbances: Already known in the field of lumbar and cervical spine disorders the assessment and evaluation of motor control also seems to be an integral part of an orofacial rehabilitation program. Standardized movement control exercises can be assessed and trained as well, whereas also mirror therapy seems to play an important role in the rehabilitation (see fig.2 and

|

Fig 2. Face motor exercises (from von Piekartz and Paris-Alemany, 2021

|

Fig 3. Face motor exercises (from von Piekartz and Paris-Alemany, 2021). |

Psychological and emotional components

Adopting a biopsychosocial approach within the CRAFTA® framework, it is crucial to acknowledge and address cognitive and emotional disturbances to comprehensively understand and treat a patient's issue. There are notable links between the aforementioned disorders and various psychological and emotional factors. These include catastrophizing, fear-avoidance behaviors, kinesiophobia, difficulties in recognizing facial emotions, alexithymia, as well as depression and anxiety. These psychological states can further lead to sleep disturbances and overall physical deconditioning (Haas et al., 2013; Kindler et al., 2018; Lei et al., 2015; Pedrosa Gil et al., 2008; Slade et al., 2016). It is important to remember that addressing these psychological dimensions often requires specialized professionals, such as psychologists, psychiatrists, or psychotherapists. This is because there are significant connections between somatosensory and sensorimotor issues and these emotional, cognitive-affective aspects.

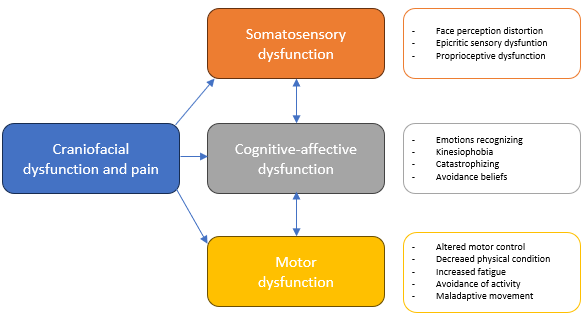

This graph below illustrates the dysfunctional aspects of craniofacial pain and their corresponding dysfunctions or distortions, in line with the knowledge presented(fig 4)

Fig 4. Dysfunctional aspects of craniofacial pain and their corresponding dysfunctions or distortions (adapted from von Piekartz and Paris-Alemany, 2021).

Topics included in the training of a CRAFTA®-Certified Physical Therapist

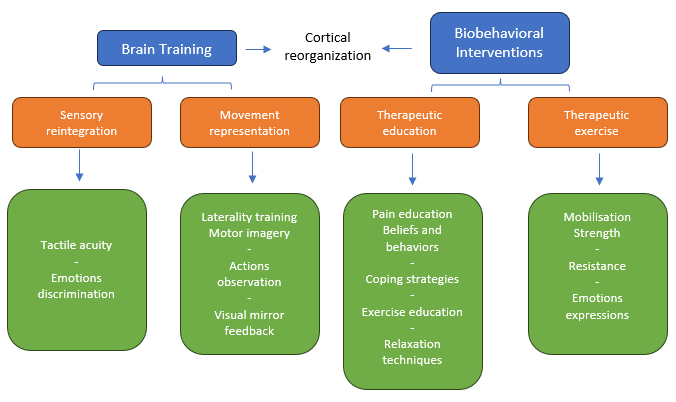

We covered two primary strategies, specifically brain training and biobehavioral interventions, along with four key elements in the assessment and treatment protocol.

- somatosensory reintegration (tactile and discriminative),

- movement representation techniques,

- therapeutic exercise (motor training),

- therapeutic patient education (to reinforce the other interventions from a behavioral point of view).

For a better overview the graph(fig. 5) concludes the above-mentioned aspects:

Fig 5. Overview of braintraining in combination with biobehavioural interventions (adapted from von Piekartz and Paris-Alemany, 2021).

In the CRAFTA® training program, participants begin by learning to evaluate and assess orofacial conditions from a comprehensive point of view, incorporating both structural and functional assessments. This includes:

- The application of manual techniques and motor control elements, as well as aiding in the reduction of somatosensory distortions.

- Advanced courses delve into body image considerations and explore motor control exercises. These are combined with discussions on pain management strategies and the implementation of graded activity methods.

- Topics like facial emotion recognition and laterality are covered in the advanced courses.

- Additionally, there's a specific online course that aligns with a unique app developed for this purpose. More information can be found at http://www.myfacetraining.com.

Systematic orofacial somatosensory training can improve mood, motor expression, and function.

References:

- Aaron, R. V., Fisher, E. A., de la Vega, R., Lumley, M. A., & Palermo, T. M. (2019). Alexithymia in individuals with chronic pain and its relation to pain intensity, physical interference, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 160(5), 994-1006. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001487

- Breckenridge, J. D., McAuley, J. H., Butler, D. S., Stewart, H., Moseley, G. L., & Ginn, K. A. (2015). Shoulder left/right judgment task: development and establishment of a normative dataset. Physiotherapy, 101, e169-e170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.323

- Catley, M. J., Tabor, A., Wand, B. M., & Moseley, G. L. (2013). Assessing tactile acuity in rheumatology and musculoskeletal medicine--how reliable are two-point discrimination tests at the neck, hand, back and foot? Rheumatology (Oxford), 52(8), 1454-1461. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket140

- Dagsdóttir, L. K., Bellan, V., Skyt, I., Vase, L., Baad-Hansen, L., Castrillon, E., & Svensson, P. (2018). Multisensory modulation of experimentally evoked perceptual distortion of the face. J Oral Rehabil, 45(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12581

- Di Tella, M., & Castelli, L. (2016). Alexithymia in Chronic Pain Disorders. Curr Rheumatol Rep, 18(7), 41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0592-x

- Elsig, S., Luomajoki, H., Sattelmayer, M., Taeymans, J., Tal-Akabi, A., & Hilfiker, R. (2014). Sensorimotor tests, such as movement control and laterality judgment accuracy, in persons with recurrent neck pain and controls. A case-control study. Man Ther, 19(6), 555-561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2014.05.014

- Haas, J., Eichhammer, P., Traue, H. C., Hoffmann, H., Behr, M., Crönlein, T., Pieh, C., & Busch, V. (2013). Alexithymic and somatisation scores in patients with temporomandibular pain disorder correlate with deficits in facial emotion recognition. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 40(2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12013

- Hosseini, S. A., & Padhy, R. K. (2022). Body Image Distortion. In StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Kindler, S., Schwahn, C., Terock, J., Mksoud, M., Bernhardt, O., Biffar, R., Völzke, H., Metelmann, H. R., & Grabe, H. J. (2018). Alexithymia and temporomandibular joint and facial pain in the general population. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12748

- La Touche, R., Cuenca-Martínez, F., Suso-Martí, L., García-Vicente, A., Navarro-Morales, B., & Paris-Alemany, A. (2020). Tactile trigeminal region acuity in temporomandibular disorders: A reliability and cross-sectional study. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 47(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12870

- Lei, J., Liu, M.-Q., Yap, A. U. J., & Fu, K.-Y. (2015, March 30). Sleep Disturbance and Psychologic Distress: Prevalence and Risk Indicators for Temporomandibular Disorders in a Chinese Population. https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.1301

- LeResche, L. (1997). Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: Implications for the investigation of etiologic factors. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine: An Official Publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists, 8(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/10454411970080030401

- Lipton, J., Ship, J., & Larach-Robinson, D. (1993). Estimated Prevalence and Distribution of Reported Orofacial Pain in the United States. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 124(10), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0200

- Linder, M., Michaelson, P., & Roijezon, U. (2016). Laterality judgments in people with low back pain--A cross-sectional observational and test-retest reliability study. Man Ther, 21, 128-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.07.001

- Luedtke, K., Adamczyk, W., Mehrtens, K., Moeller, I., Rosenbaum, L., Schaefer, A., . . . Wollesen, B. (2018). Upper cervical two-point discrimination thresholds in migraine patients and headache-free controls. Journal of Headache & Pain, 19(1), 47. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0873-z

- Luomajoki, H., & Moseley, G. L. (2011). Tactile acuity and lumbopelvic motor control in patients with back pain and healthy controls. Br J Sports Med, 45(5), 437-440. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.060731

- Maarbjerg, S., Wolfram, F., Heinskou, T. B., Rochat, P., Gozalov, A., Brennum, J., . . . Bendtsen, L. (2017). Persistent idiopathic facial pain - a prospective systematic study of clinical characteristics and neuroanatomical findings at 3.0 Tesla MRI. Cephalalgia, 37(13), 1231-1240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102416675618

- Parsons, L. M. (1987). Imagined spatial transformations of one's hands and feet. Cogn Psychol, 19(2), 178-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(87)90011-9

- Pedrosa Gil, F., Ridout, N., Kessler, H., Neuffer, M., Schoechlin, C., Traue, H. C., & Nickel, M. (2008). Facial emotion recognition and alexithymia in adults with somatoform disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 25(11), E133–E141. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20440

- Piekartz, H., Wallwork, S. B., Mohr, G., Butler, D. S., & Moseley, G. L. (2015). People with chronic facial pain perform worse than controls at a facial emotion recognition task, but it is not all about the emotion. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 42(4), 243-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12249

- Reinersmann, A., Haarmeyer, G. S., Blankenburg, M., Frettloh, J., Krumova, E. K., Ocklenburg, S., & Maier, C. (2010). Left is where the L is right. Significantly delayed reaction time in limb laterality recognition in both CRPS and phantom limb pain patients. Neurosci Lett, 486(3), 240-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.062

- Slade, G. D., Ohrbach, R., Greenspan, J. D., Fillingim, R. B., Bair, E., Sanders, A. E., Dubner, R., Diatchenko, L., Meloto, C. B., Smith, S., & Maixner, W. (2016). Painful Temporomandibular Disorder. Journal of Dental Research, 95(10), 1084–1092. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516653743

- Stamper, G. C., & Johnson, T. A. (2015). Auditory Function in Normal-Hearing, Noise-Exposed Human Ears. Ear and Hearing, 36(2), 172. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000107

- Stanton, T. R., Lin, C. W., Bray, H., Smeets, R. J., Taylor, D., Law, R. Y., & Moseley, G. L. (2013). Tactile acuity is disrupted in osteoarthritis but is unrelated to disruptions in motor imagery performance. *Rheumatology (Oxford), 52*(8), 1509-1519. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ket139

- von Piekartz, H., & Mohr, G. (2014). Reduction of head and face pain by challenging lateralization and basic emotions: a proposal for future assessment and rehabilitation strategies. *Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy (Maney Publishing), 22*(1), 24-35. doi:10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000063

- von Piekartz, H., Lüers, J., Daumeyer, H., & Mohr, G. (2017). [Is kinesiophobia associated with changes in left/right judgment and emotion recognition during a persisting pain condition? : A cross-sectional study]. *Schmerz (Berlin, Germany), 31*(5), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-017-0220-3

- von Piekartz, H., & Paris-Alemany, A. (2021). Assessment and Brain Training of Patients Experiencing Head and Facial Pain with a Distortion of Orofacial Somatorepresentation: A Narrative Review. *Applied Sciences, 11*(15),Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/15/6857

Manual Cranial Therapy

Cranial manual therapy means: assessment and treatment of the cranium..

Read more..

Pain Education

“pain neuroscience education (PNE)” or “Explain Pain” is a therapeutic tool...

Read more..

Headache (HA) in children

What can the (specialized) physical therapist mean for this pain suffering group..

Read more..

Assessment Bruxism

Assessment and Management of Bruxism by certificated CRAFTA® Physical Therapists

Read more..

Clinical classification of cranial neuropathies

Assessment and Treatment of cranial neuropathies driven by clinical classification..

Read more..

Functional Dysphonia

Functional Dysphonia (FD) is a condition characterized by voice problems in the absence of a physical laryngeal pathology.

Read more..

Body Image and Distorted Perception

Body Image and Distorted Perception of One's Own Body – What Does This Mean?

Read more..

TMD in Children

TMD affects not only adults, but it also occurs frequently in children and adolescents..

Read more..